The Important Lesson You’re Missing from the Facebook Data Debacle

Posted onFacebook didn’t fail to protect user data in accordance with its terms of service. Facebook didn’t fail to make itself transparent enough so that users understood how their data would be used.

Facebook failed to keep its promises to its users.

This is the lesson you and your company can take away from this debacle. It’s vitally important to you because, while it’s really hard for most people to leave Facebook, I’m pretty sure it is not nearly as hard for most of your customers to leave you, should you break your promises to them.

How did Facebook break its promises?

To answer that, let’s start by defining a promise. We think of promises as commitments we make to other people about things we intend to do. But for a business, a promise is more than that.

A promise is made when a business commits to using its capabilities to meet a need or aspiration of its customer.

In the B2B world, this might look like something as simple as a marketing automation vendor promising its product will always get your campaigns scheduled and launched correctly, and tracked as you instructed. Or it might look like an intelligent system promising to understand your customer interactions to help you identify your happiest and least happy customers.

In the second example, if the system got it wrong enough of the time so it became unreliable to use as a basis for customer-related decisions, then it would be breaking its promise. I am not suggesting it needs to be perfect. But it does need to be consistent and reliable.

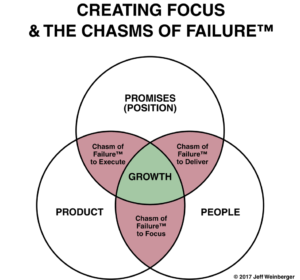

You make promises to your customers every day. Some have to do with your product or service. Some with how your people interact with and support them. Others might be about what you are going to do for them in the future. All these promises are important and are the reasons your customer bought from you in the first place. The quickest way to lose a customer is to break a promise you’ve made. The easiest way is to fail to understand what promises your customer thinks you’ve made.

Back to Facebook

Facebook’s core promise is to connect people to their friends and to things of interest to them (news, events, companies, etc.). Part of that promise is that, in exchange for doing this at no cost, Facebook will show you paid advertising, based on the data you provide.

That last bit is important. Most people know they are providing data such as their name, location and age. Most people don’t know they are providing information about their preferences, political views, browsing habits and so much more.

The promise of a free service in exchange for advertising is not a hard concept. Ad retargeting is. A spokesperson for Mozilla said it well: “Tech companies can’t expect most of their users to understand how their service works.”

That’s where Facebook went wrong.

Facebook works on the premise that, by publishing a terms-of-service document and making settings available to control use of personal data, every user will know exactly what it all means. That’s not even close to true.

In fact, most Facebook users think Facebook keeps their information relatively private, and that by having a password, only they can get to the data they enter. That’s also not even close to true. It’s even reasonable for any Facebook user to believe the persona information they enter is a kind of a public secret among them and their friends. Even many sophisticated Facebook users — ones who understand how an advertising-supported model works — with whom I’ve spoken are surprised at how much data Facebook has shared, and how freely Facebook’s advertisers are permitted to use and distribute that data.

And there’s the problem.

The gulf between what Facebook thinks it promised and what its users think it promised is enormous. Facebook didn’t fail to live up to its terms of service. It didn’t fail to provide settings and promote them. It failed to understand what its users expected and how to act on those expectations.

We in the tech industry take a laissez-faire attitude toward our promises to our customers. Most EULAs say products are delivered “as-is” and make it clear they may not work. Most terms-of-service documents disclaim any responsibility for failure of the product.

That may protect your company legally. But it won’t keep customers. Remember my first rule of customer service?

“If you’re quoting your terms of service, you’re wrong.”

What you should do:

Talk to your customers. Make absolutely sure you know what they think you promised to them. Make sure they know you are, in fact, promising. Make sure there is no gap whatsoever between those understandings.

Then keep those promises. Consistently.

Because, if a Facebook-like debacle happens to you, you will probably not end up testifying before Congress. But you will almost certainly lose a significant number of customers.

To learn more about doing it the right way, check out my five-part series showing how customer trust is the key to growth.