Caution: Predictive Analytics May Miss One Important Thing

Posted onPredictive analytics is, without a doubt, the new big thing in marketing. It’s how we marketers are putting so-called big data to work to help us find, target, and sell to the right customers at the right time. I’ve written about this before; any time we rely on technology or process to tell us about our customers’ preferences, habits, or needs, we run the risk of missing out on one critical element of our customers’ decision-making. Our customers are human and, therefore, somewhat unpredictable.

Many years ago, I worked with a company that created customized news feeds. Customers would select their areas of interest, and each day, the company would sort items from a range of newswires (yes, this is before social media!) and send each customer a custom collection of articles, press releases, and other news items.

A general concern others and I raised about the trend toward more personalization (which is still ongoing) is that people would miss out on items of general interest. In those days, when I read the newspaper, I would seek out sections of particular interest to me, but I would also read the front page and often catch other items on my way to my sections. This exposed me to news, information, and thinking outside my specific area of interest. In particular, reading the front page gave me a sense of what was collectively considered important (as filtered by an editor, granted, but one whose interest likely was matching the collective interest). This provided a common understanding of the world and important events of the day. With an entirely customized newswire (or, in today’s terms, a group of Facebook friends with whom you completely agree), you create your own unique understanding of the world around you, and you become less aware of what is outside your bubble (and in some cases, less able to understand it).

One of our goals as marketers is to influence behavior, particularly toward buying our products and services. One way to do this is to create some elements of a bubble around the target buyers so they see more of your offerings than anything else and more messages encouraging the lifestyle associated with your offerings. That creates stronger associations with the promise of the brand and results in brand loyalty.

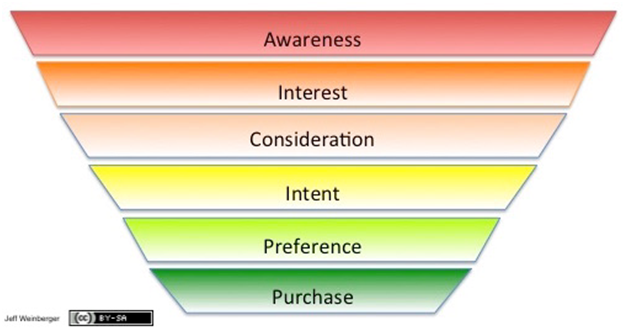

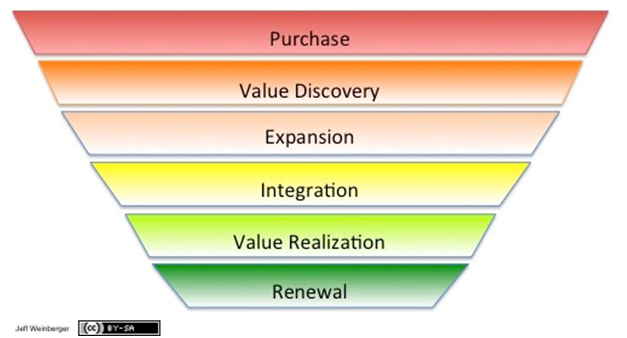

We observe the actions customers take and focus on the ones that make them most likely to deepen their association with our brand and all of the things for which that brand stands. That creates the customer journey.

Once we know all that, we work hard to influence customers to take the next step on their journey toward becoming a brand loyalist and buying more and more from us.

Dealing with the myriad actions, possible paths, probable journeys, and the wide range of customer tastes and behaviors has been nearly impossible until technology stepped in to give us ways to store and analyze all that data. Enter big data and predictive analytics.

We now have computer systems that tell us—if a customer has a certain set of tastes and preferences, and then takes a given action (or a series of actions)—what the most effective way to get them to take the next action is. So we do that. Then we see many of those customers taking the hoped-for action.

Enhancing the Impact of Predictive Analytics

One of my favorite themes is to remind marketers that your instinct—your intuitive understanding—goes far beyond the analysis of any computer system. You will not always be right, but your intuition provides a strong sanity check.

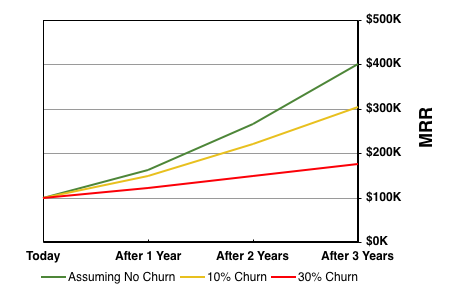

For example, your predictive analytics might suggest prospects who end up buying from you always take a specified action several steps prior to purchasing. This might be true. But you might also notice there is a large drop-off rate right before that step—only a small number of prospects in your funnel move to that step. Your analytics don’t tell you this because you’ve told your systems to answer the question of what causes people to buy, so it looks at the outcome and works backward. It takes human powers of observation to look at the funnel from a different perspective.

I rely on my systems and the analyses they produce to tell me how my programs are working. I set them up to give me data-driven answers to a variety of questions, including the question of what actions are most influential in converting prospects to paying customers.

But I always look at the data myself. I look for anomalies. I look for things that might not be answered by my systems the way I’ve set them up. I look for things I’ve otherwise overlooked. Some of those insights have led to opportunities I would not have seen otherwise.

In short, I use my own experienced intuition to make the final call about what is working, what is not, and where I should look next to improve my efforts.

Don’t miss out on this one critical factor. Don’t let your predictive analytics and automation systems take over your marketing. There may come a day when intelligent systems can do this for us, but for now, this is your job. It’s where your value gets added. Using your own experienced intuition is what makes the difference between good marketing and great marketing. Don’t give that up.